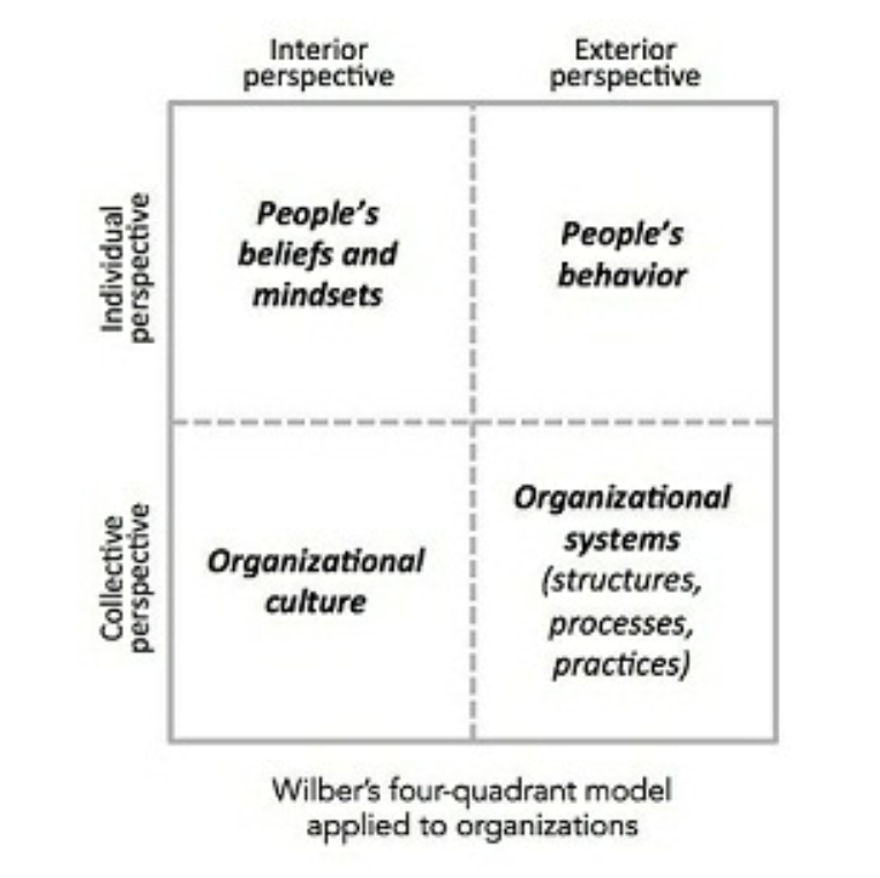

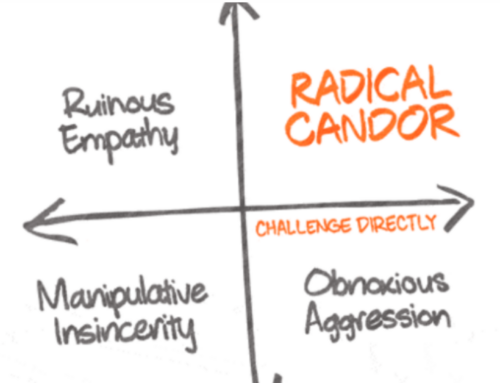

How culture, systems, and worldviews interact: the four quadrants: Which side of the argument has got it right, then? Is it best to rely on the tangible elements of structure or the intangible substance of culture? The answer has profound implications for leaders, and yet this question is often discussed without much grounding. Ken Wilber’s four-quadrant model can provide a solid basis for this discussion through a few simple yet powerful distinctions. Wilber, the founder of Integral Theory, uncovered a profound truth about the nature of reality: any phenomenon has four facets and can be approached from four sides. To understand it well, we should both look at it objectively from the outside (the tangible, measurable, exterior dimension) and we should sense the phenomenon from the inside (the intangible interior dimension of thoughts, feelings, and sensations). We must also look at the event in isolation (the individual dimension) and look at the event in its broader context (the collective dimension). Only when we look at all four aspects will we get what Wilber calls an integral grasp of reality.

Wilber’s insight, applied to organizations, means that we should look at 1) people’s mindsets and beliefs; 2) people’s behavior; 3) the organizational culture; and 4) the organizational structures, processes, and practices.

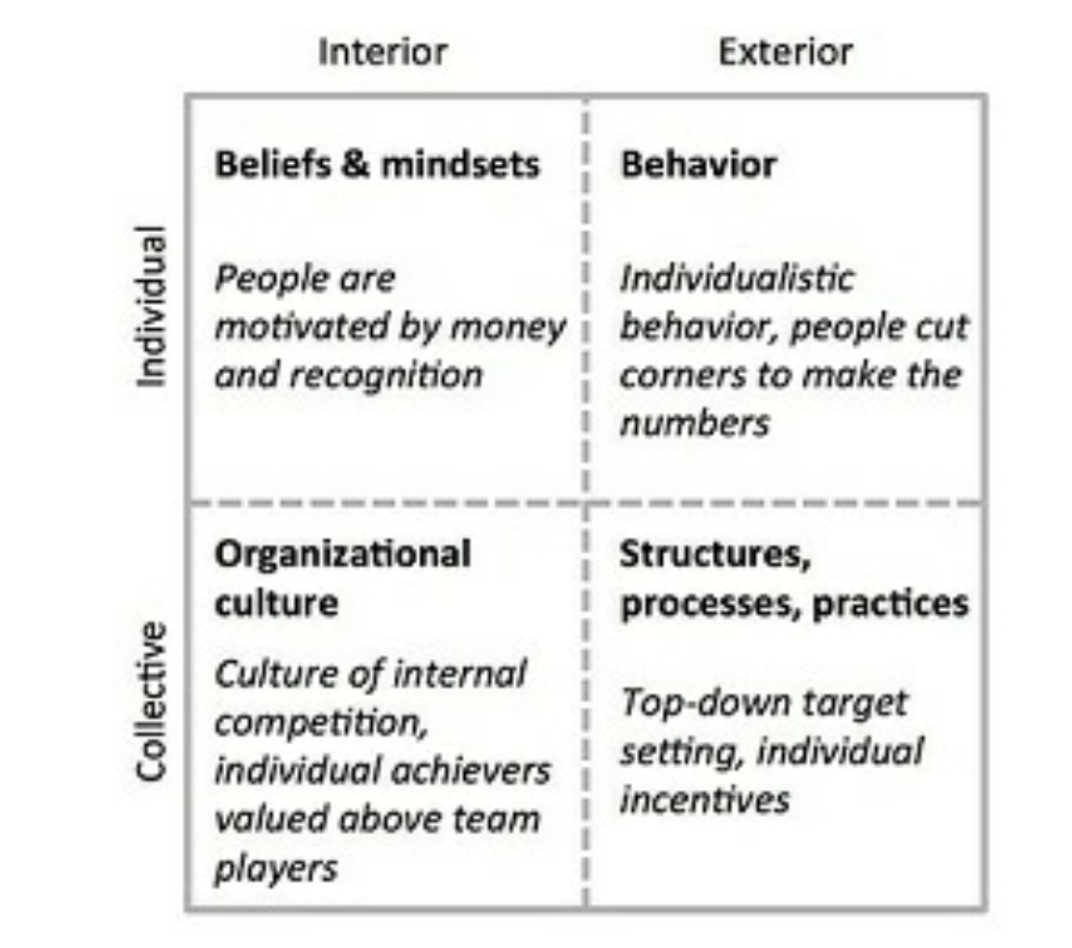

A practical example can help us better understand the model. Let’s take the common (Orange) belief that people are motivated by money and recognition. Leaders who hold such a belief (upper-left corner) will naturally put in place incentive systems that match their belief: people should be given ambitious targets and a lofty bonus if they reach them (lower-right quadrant). The belief and the incentives will likely affect people’s behavior throughout the organization: people will behave individualistically; they will be tempted to cut corners if needed to make the numbers (upper-right quadrant). And a culture will develop that esteems great achievers above team players (lower-left corner).

The four-quadrant model shows how deeply mindsets, culture, behavior, and systems are intertwined. A change in any one dimension will ripple through the other three. Yet very often, we don’t grasp the full picture. Amber and Orange only see the “hard” measurable outer dimensions (the right-hand quadrants), and neglect the “soft” inner dimensions (the left-hand quadrants). Green’s breakthrough is to bring attention to the inner dimensions of mindsets and culture, but often the pendulum swings too far the other way. Green Organizations tend to focus so much on culture that they neglect to rethink structure, processes, and practices. (Edgar Schein, one of the academic pioneers in the field of organizational culture, once said, “The only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage culture,” a typical example of that extreme school of thought.) Companies like Southwest Airlines or Ben & Jerry’s keep many of the systemic elements from traditional hierarchical structures (the lower-right quadrant), but also put in place a culture (lower-left quadrant) that asks managers to behave in non-hierarchical ways, to be servant leaders who listen to their subordinates and empower them.

Hierarchical structures with non-hierarchical cultures—it’s easy to see that the two go together like oil and water. That is why leaders in these companies insist that culture needs constant attention and continuous investment. In a hierarchical structure that gives managers power over their subordinates, a constant investment of energy is required to keep managers from using that power in hierarchical ways. Stop investing in culture, and the structurally embedded hierarchy is likely to take the upper hand.

Self-managing structures transcend the issue of culture versus systems. Inner and outer dimensions, culture and systems, work hand in hand, not in opposite directions. Power is naturally distributed and there is no need to invest time and effort to prod middle managers to “empower” people below them. If managers have no weapons, there is no need to invest in a culture that keeps people from using their weapons. This is the experience that David Allen, of Getting Things Done fame, had when he adopted Holacracy in his consulting and training firm, the David Allen Company:

As we’ve distributed accountability down and throughout the organization, I’ve had much less of my attention on the culture. In an operating system that’s dysfunctional, you need to focus on things like values in order to make that somewhat tolerable, but if we’re all willing to pay attention to the higher purpose, and do what we do and do it well, the culture just emerges. You don’t have to force it.

Does this mean, then, that culture is less relevant in Teal Organizations? Brian Robertson gives an eloquent answer: Culture in self-managing structures is both less necessary and more impactful than in traditional organizations. Less necessary because culture is not needed to overcome the troubles brought about by hierarchy. And more impactful, for the same reason—no energy is gobbled up fighting the structure, and all energy and attention brought to organizational culture can bear fruit. From a Teal perspective, organizational culture and organizational systems go hand in hand, and are facets of the same reality—both are equally deserving of conscious attention.

The culture of Teal Organizations

Is there a specific culture that all Teal Organizations share? The research shows that Teal Organizations can have greatly different cultures, but a number of cultural elements tend to be present in all of them.

The context in which a company operates, and the purpose it pursues, calls for a unique, specific culture. Let’s contrast, for instance, the culture of RHD with that of Morning Star. RHD’s central office is as quirky and colorful as any you are likely to have ever seen. Picture a few interlocking former warehouses converted into one giant open office space. The walls are painted in bright orange, but you can see the bright color only in those places where there are no oversized photographs of RHD’s customers, paintings from some of the mentally ill patients it serves, or posters employees have put up featuring quotes or community activities they organize. The waiting area for visitors consists of a few chairs in the middle of this vibrant craze, next to a small pond where rather eccentric-looking plastic ducks proudly float in place of the goldfish that perhaps once swam there.

The contrast with Morning Star’s offices in their factories and headquarters couldn’t be starker. Everything there exudes quality and tidiness. Walls are painted white, paintings are elegantly framed, and papers are pinned only on the intended message boards.

The two companies work in very different contexts, which helps explain the very different culture reflected in their office buildings. RHD’s vibrant central office reveals a culture where people are encouraged to accept other people’s quirkiness as much as their own. RHD’s purpose is to help people with such issues as mental diseases, mental disabilities, homelessness, and substance addiction build better lives for themselves. Central to achieving that purpose is the ability of employees to offer their consumers a caring, nonjudgmental presence. It helps if people don’t define each other in binary categories—the normal employees and not-so-normal customers—and if instead everyone is seen as unique and quirky, whether employee or customer. Morning Star, on the other hand, operates in the food industry, with exacting standards of hygiene. A crazy, buzzing environment like RHD’s would be anathema there. In the factory, things must be spotless, so that any problem in the process becomes immediately apparent, and that ethos pervades office spaces as well.

Context and purpose drive the culture that is called for in an organization. But beyond the unique culture of each company, there are a number of common traits linked to the developmental stage of an organization. All Amber Organizations, to one extent or another, value the following of orders as part of their culture; a norm that loses its meaning in self-managing Teal Organizations. Below are some of the commonly shared cultural elements—norms, assumptions, concerns—I have encountered in the pioneer organizations studied for this book, elements that also seem consistent with the Evolutionary-Teal worldview. The list is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive, but it can provide food for thought.

SELF-MANAGEMENT

Trust

- We relate to one another with an assumption of positive intent.

- Until we are proven wrong, trusting co-workers is our default means of engagement.

- Freedom and accountability are two sides of the same coin.

Information and decision-making

- All business information is open to all.

- Every one of us is able to handle difficult and sensitive news.

- We believe in collective intelligence. Nobody is as smart as everybody. Therefore all decisions will be made with the advice process.

Responsibility and accountability

- We each have full responsibility for the organization. If we sense that something needs to happen, we have a duty to address it. It’s not acceptable to limit our concern to the remit of our roles.

- Everyone must be comfortable with holding others accountable to their commitments through feedback and respectful confrontation.

WHOLENESS

Equal worth

- We are all of fundamentally equal worth.

- At the same time, our community will be richest if we let all members contribute in their distinctive way, appreciating the differences in roles, education, backgrounds, interests, skills, characters, points of view, and so on.

Safe and caring workplace

- Any situation can be approached from fear and separation, or from love and connection. We choose love and connection.

- We strive to create emotionally and spiritually safe environments, where each of us can behave authentically.

- We honor the moods of … [love, care, recognition, gratitude, curiosity, fun, playfulness …].

- We are comfortable with vocabulary like care, love, service, purpose, soul … in the workplace.

Overcoming separation

- We aim to have a workplace where we can honor all parts of us: the cognitive, physical, emotional, and spiritual; the rational and the intuitive; the feminine and the masculine.

- We recognize that we are all deeply interconnected, part of a bigger whole that includes nature and all forms of life.

Learning

- Every problem is an invitation to learn and grow. We will always be learners. We have never arrived.

- Failure is always a possibility if we strive boldly for our purpose. We discuss our failures openly and learn from them. Hiding or neglecting to learn from failure is unacceptable.

- Feedback and respectful confrontation are gifts we share to help one another grow.

- We focus on strengths more than weaknesses, on opportunities more than problems.

Relationships and conflict

- It’s impossible to change other people. We can only change ourselves.

- We take ownership for our thoughts, beliefs, words, and actions.

- We don’t spread rumors. We don’t talk behind someone’s back.

- We resolve disagreements one-on-one and don’t drag other people into the problem.

- We don’t blame problems on others. When we feel like blaming, we take it as an invitation to reflect on how we might be part of the problem (and the solution).

PURPOSE

Collective purpose

- We view the organization as having a soul and purpose of its own.

- We try to listen in to where the organization wants to go and beware of forcing a direction onto it.

Individual purpose

- We have a duty to ourselves and to the organization to inquire into our personal sense of calling to see if and how it resonates with the organization’s purpose.

- We try to imbue our roles with our souls, not our egos.

Planning the future

- Trying to predict and control the future is futile. We make forecasts only when a specific decision requires us to do so.

- Everything will unfold with more grace if we stop trying to control and instead choose to simply sense and respond.

Profit

- In the long run, there are no trade-offs between purpose and profits. If we focus on purpose, profits will follow.

Supporting the emergence of an organization’s culture

How does an organizational culture emerge, and what makes one culture more powerful than another? In most companies, the culture simply reflects the assumptions, norms, and concerns of the organization’s founders or leaders, with all their lights and shadows.

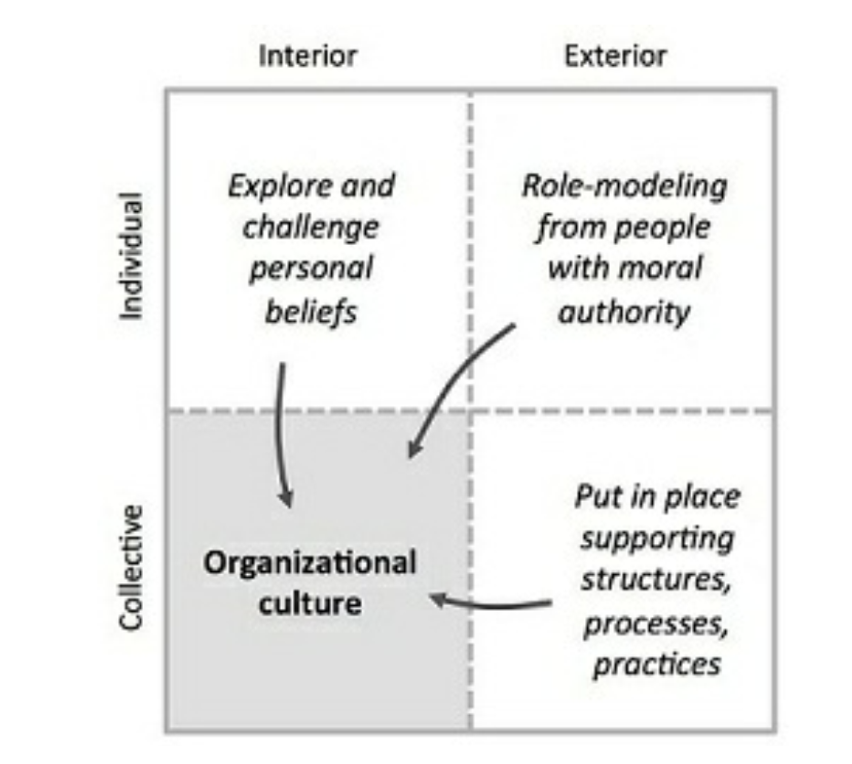

From an Evolutionary-Teal perspective, an organization is a living organism with its own life force, and it should be allowed to have its own autonomous culture, distinct from the assumptions and concerns of its founders and leaders. Everyone should be invited to listen in to the culture that best fits the organization’s context and the purpose it pursues (for instance using large group processes that were described in the previous chapter). When there is clarity as to the culture that is most supportive of the organization’s context and purpose, the question becomes: how can a group of people consciously bring about that culture? Wilber’s framework provides a simple answer: to shape the culture (the lower-left quadrant), you can pursue three avenues in parallel:

- Put supportive structures, practices, and processes in place (lower-right quadrant)

- Ensure that people with moral authority in the company role-model the behavior associated with the culture (upper-right quadrant)

- Invite people to explore how their personal belief system supports or undermines the new culture (upper-left quadrant)

As an illustration, let’s assume you feel your organization calls for a mood of gratitude and celebration.

- You can try to put in place recurring practices (lower-right quadrant) that evoke a mood of gratitude and celebration, such as, for example, ESBZ’s “praise meeting“ or Ozvision’s “day of thanking“. Maintain these practices for a few months and the company will develop a culture where people feel it is natural to praise and thank each other spontaneously.

- You can call on the company’s most respected figures—the people that others look up to—to double down for a while on thanking their colleagues and celebrating effort and achievements.

- You can also hold workshops where people explore how they personally relate to gratitude and celebration. Some people naturally thank and praise colleagues, without even thinking about it. Others don’t—thanking or celebrating people might feel awkward to them, perhaps because they grew up in a family where such things weren’t spoken about, for example. Coaching can help uncover limiting beliefs that hold people back from engaging with others in gratitude and celebration.

In summary, what is the place of organizational culture in Teal Organizations? With self-managing structures and processes in place, and with practices to pursue wholeness and purpose, culture becomes both less necessary and more impactful. The culture of the organization should be shaped by the context and the purpose of the organization, not by the personal assumptions, norms, and concerns of the founders and leaders. In self-managing structures, chances are this happens naturally and organically because everyone, not just the people at the top, participates in sensing what is needed. If there is a sense, however, that an organization’s culture needs to further evolve, colleagues can dedicate time, possibly using a large group process, to listen in to the culture that the context and purpose call for.

While many aspects of the needed culture will be unique to the organization, some characteristic elements of the Evolutionary-Teal stage of development are likely to emerge. Teams can refer to the list provided earlier in this chapter to stimulate reflection.

There are three ways to help put new cultural elements in place: through practices that support corresponding behavior, through role-modeling by colleagues with moral authority, and by creating a space where people can explore how their belief system supports or undermines the new culture.

Philosophically, Teal’s breakthrough is to give all four quadrants their due—culture, systems, mindsets, and behavior. Previous paradigms focused on the “hard” dimension at the expense of the “soft” or vice-versa. It’s a safe bet to assume that the future belongs to organizations where “hard” and “soft” work hand in hand, and reinforce each other in service of the organization’s purpose.